Inversion of the Yield Curve: Recession ahoy?

Looking at a so-called normal yield curve, there is a positive correlation between the maturity of bonds and the expected return. This is intuitively conclusive, as maturities entail a higher degree of uncertainty regarding the issuer’s ability (and willingness) to repay, as well as a form of maturity premium – so as an investor, you would expect a higher return.

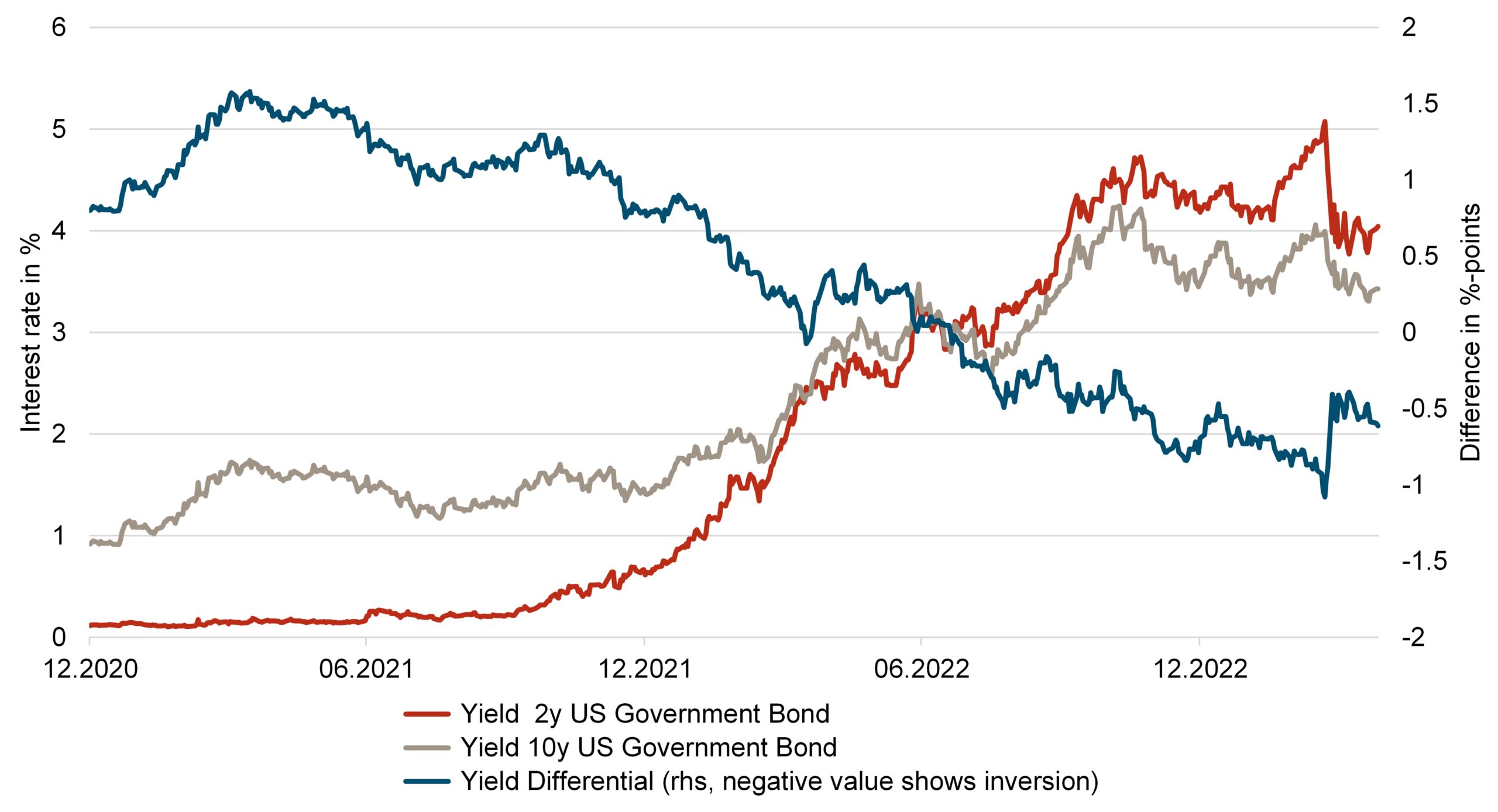

But if you look at the current yield curves in different currency areas, the picture is different: some of the curves are very flat – long maturities do not yield more than shorter ones – or are even inverted. In such a case, short maturities yield higher returns than longer maturities. Market observers are sensitive to such a counterintuitive situation, as inverted yield curves have often preceded recessions in the past. So, is the interest rate market currently heralding the coming of a recession?

Looking back over the past decades, it can be said that almost every recession was preceded by an inversion. Conversely, however, not every inversion has necessarily been followed by a recession. The question also arises as to how quickly a possible recession may follow an inversion.

First, on causality: An inversion does not cause a recession to occur. Rather, the shape of the yield curve reflects factors at work in the market that, depending on the overall economic environment, are deemed to point to the need for supporting measures to prevent an economic setback.

First and foremost is the macroeconomic growth forecast anticipated by the market. Put simply, if market participants expect a weak overall picture, safe and longer-dated high-quality bonds will be favored over more growth-sensitive assets such as equities. Increased demand at the longer end stimulates prices and, as a result, interest rates drop. Also, reduced economic activity has an impact on inflation and thus real interest rates. In addition, a weak outlook fuels expectations of interest rate cuts by central banks. The long end of the yield curve reflects the path of falling short-term interest rates and is also falling accordingly.

There is another factor at play in the current situation. The current cycle of interest rate hikes is unprecedented in speed and magnitude. Due to the rapid succession of rate hikes by central banks within the past few months, a rapid rise in short-term interest rates occurred: Not only does the long end show an inhibited growth outlook – the short end has also risen significantly as a result of central bank interventions. The further interest rate steps expected by the market until recently, subsequently led to a historically pronounced inversion of the yield curves.

Ultimately, however, the extent of the inversion does not indicate when a recession will occur. The past decades also provide little information here: Historically, the time gap between an inversion and the following recession varies between six months (2019/2020) and 22 months (2006). Over the past five decades, the average time between the start of an inversion and the actual recession – when the recession actually occured – has been approximately 12 months.

An inversion is therefore not necessarily followed by a recession; to speak of a direct chronological consequence is also an exaggeration. However, the inversion can been seen as a warning signal…